MAJORS

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

- ATLAS Collaboration

- John S. Toll Research Program

- “I learned so much physics outside of my required major-related coursework doing research with Dr. Shrestha. The amount of new physics I learned—the depths into which I was able to explore particle physics—was something that I didn't know would be possible. When I was growing up, while I really liked physics, I didn't know how long I would be able to pursue it, how long I’d be able to keep studying it. Coming to Washington College I was able to study physics during my undergraduate degree and now I'm studying what I like for longer. I just want to be immersed in this field of study that I enjoy for as long as possible.”

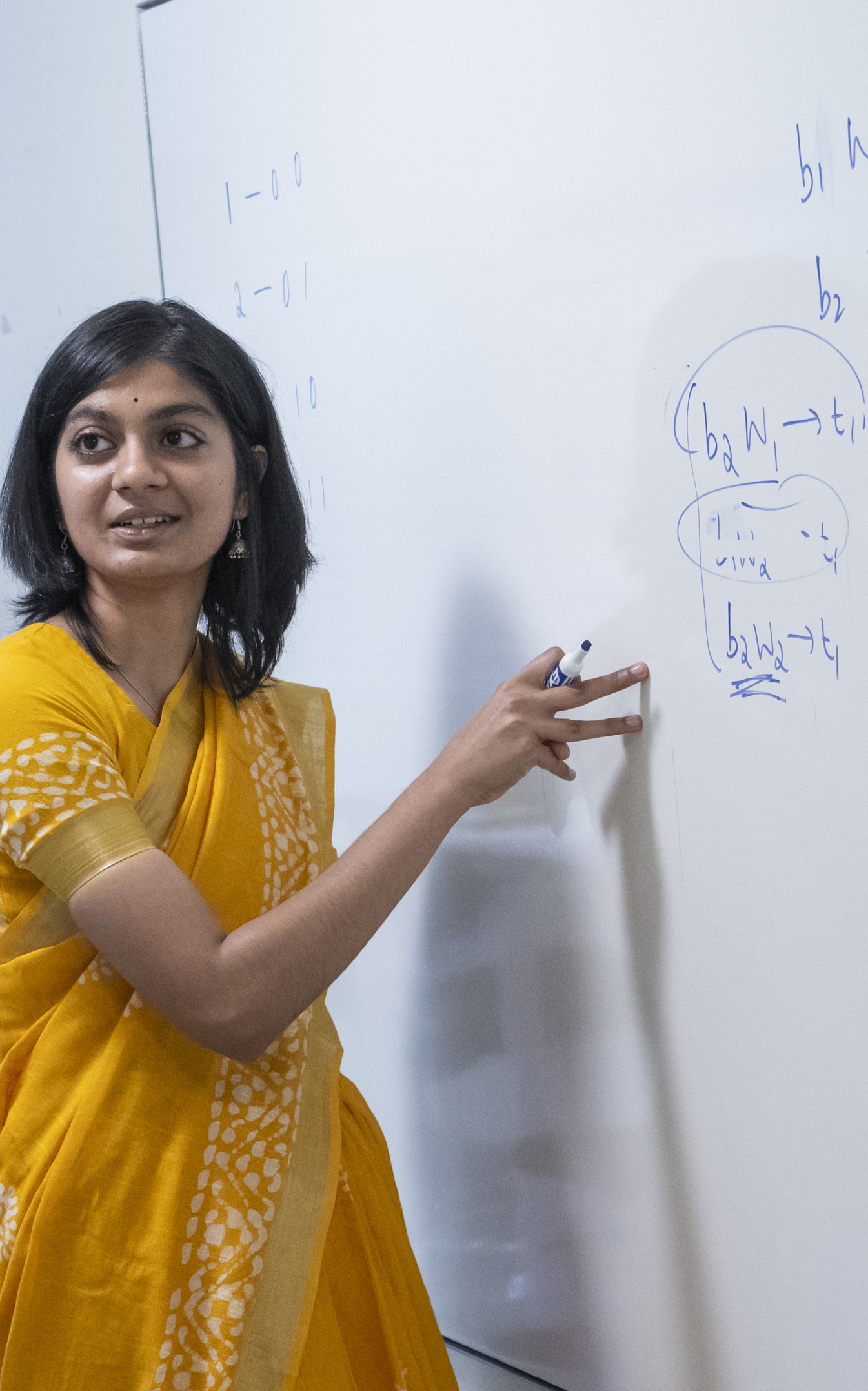

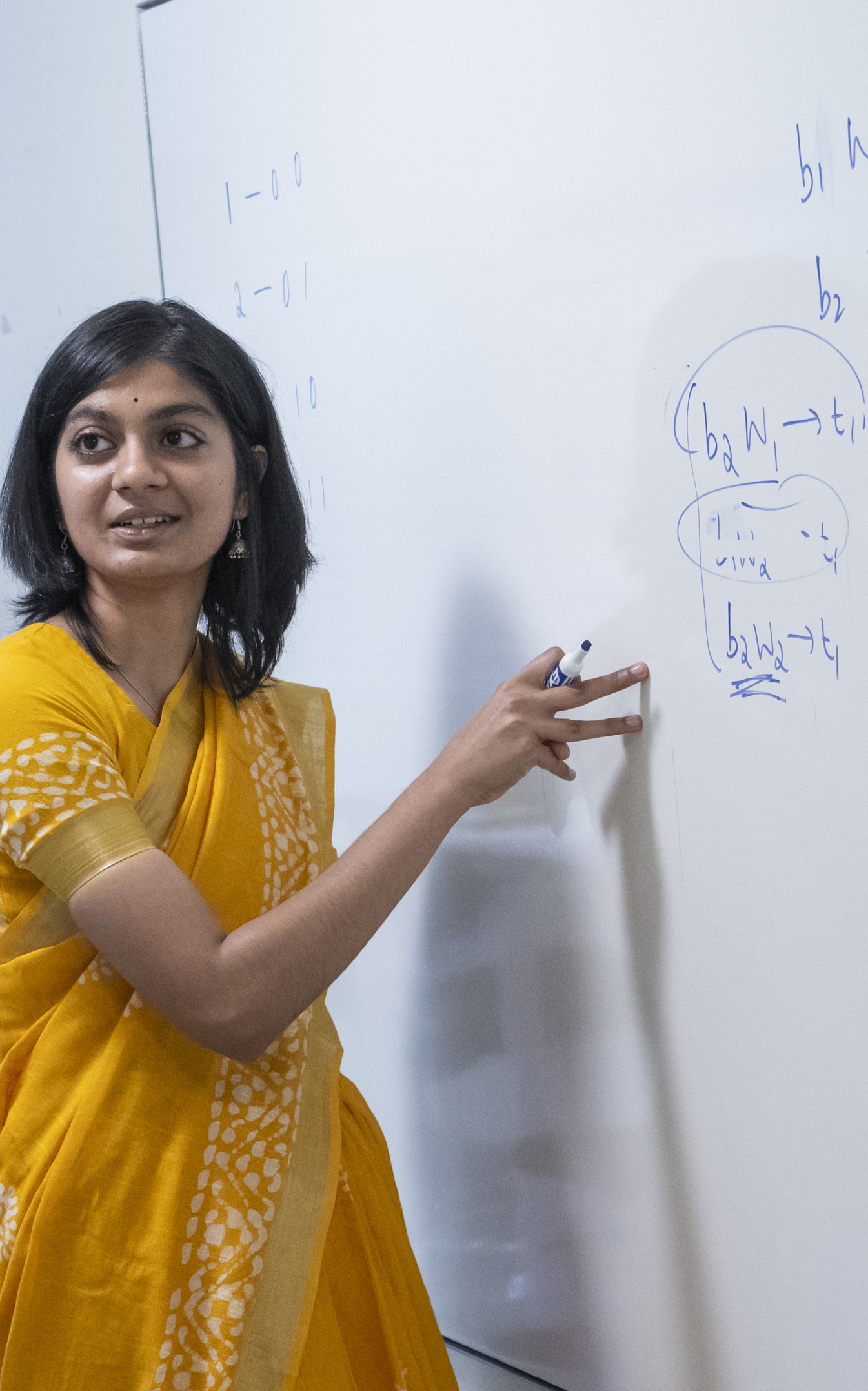

Studying Atomic Collisions

Sneha Dixit '23

Ph.D. program at the University of Nebraska at LincolnMAJORS

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

- “I learned so much physics outside of my required major-related coursework doing research with Dr. Shrestha. The amount of new physics I learned—the depths into which I was able to explore particle physics—was something that I didn't know would be possible. When I was growing up, while I really liked physics, I didn't know how long I would be able to pursue it, how long I’d be able to keep studying it. Coming to Washington College I was able to study physics during my undergraduate degree and now I'm studying what I like for longer. I just want to be immersed in this field of study that I enjoy for as long as possible.”

But Dixit actually began her work with the Large Hadron Collider while at Washington College, the result of close mentorship from Assistant Professor of Physics Suyog Shrestha, who was part of the team of 6,000 scientists whose work led to the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, resulting in the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics for theorists who predicted the existence of this particle decades before.

“I learned so much physics outside of my required major-related coursework doing research with Dr. Shrestha,” Dixit said. “The amount of new physics I learned—the depths into which I was able to explore particle physics—was something that I didn't know would be possible.”

Shrestha, and Dixit while she was at Washington, works with the Large Hadron Collider on ATLAS, the sister experiment to CMS. The two projects work in parallel but do not collaborate, using each other's results to confirm findings before publishing them if the findings have historical significance such as the discovery of the Higgs boson.

Dixit first worked with Shrestha in the summer of 2021, supported by the College's John S. Toll Research Program. In 2022 she worked with Digesh Raut, a visiting assistant professor at Washington and particle physicist on a separate research project on dark matter, but "both projects have particle physics theories in common” and studying one helped her understand the other, according to Dixit.

Not only did the complementary research opportunities deepen Dixit's knowledge, they also gave her the skills and experience to win the US ATLAS Summer Undergraduate Program for Exceptional Researchers (SUPER) award, which allowed her to continue working on Shrestha's project for eight weeks after graduation and before starting at the University of Nebraska.

The current theory underpinning scientists' understanding of nature at the smallest scale is called the Standard Model, and it explains much of how our universe works. Standard Model insights are integral to much of modern electronics. The Standard Model predicted the Higgs boson decades before its discovery. But it doesn't adequately explain everything, and Shrestha notes that as experimentalists, he and his colleagues in the ATLAS Collaboration aim to test the weaknesses of the theory to either prove or disprove certain aspects of it.

In addition to predicting the Higgs boson, the Standard Model indicates the particle should be able to interact with itself, a unique phenomenon that will result in the production of two Higgs bosons in the same proton-proton collision event. This unique property of the Higgs boson is called Higgs self-coupling, and such events are called Di-Higgs events.

At Washington, Dixit worked on simulations to study features of the Di-Higgs process that will allow physicists to measure the Higgs self-coupling. The Standard Model predicts a precise value of the Higgs self-coupling, and the experimentalists are carrying out the measurements to test if the theory is correct, or if the theory fails. Failure of the theory won't necessarily be a bad outcome, because it may lead to new developments in physics that could explain other cosmological observations, such as dark matter, that don't fit into the Standard Model. In any case, observing a Di-Higgs process is extremely rare, much rarer than observing a single Higgs boson in 2012. Shrestha says it is “like looking for a needle in a haystack of needles.”

Dixit said the experience she had at Washington was a welcome surprise, and one that allowed her to keep pursuing her passion now at the University of Nebraska.

“When I was growing up, while I really liked physics, I didn't know how long I would be able to pursue it, how long I'd be able to keep studying it,” Dixit said. “Coming to Washington, I was able to study physics during my undergraduate degree, and now I'm able to extend that period and just keep studying what I like for longer. I just want to be immersed in this field of study that I enjoy for as long as possible.”

— Mark Jolly-Van Bodegraven