Witchcraft Accusations in Early Maryland

During the 1600s, when Maryland society was just forming out of groups of immigrants primarily from the British Isles, early settlers were leaving communities in the grip of a politically- and religiously driven paranoia regarding the devil and witches.

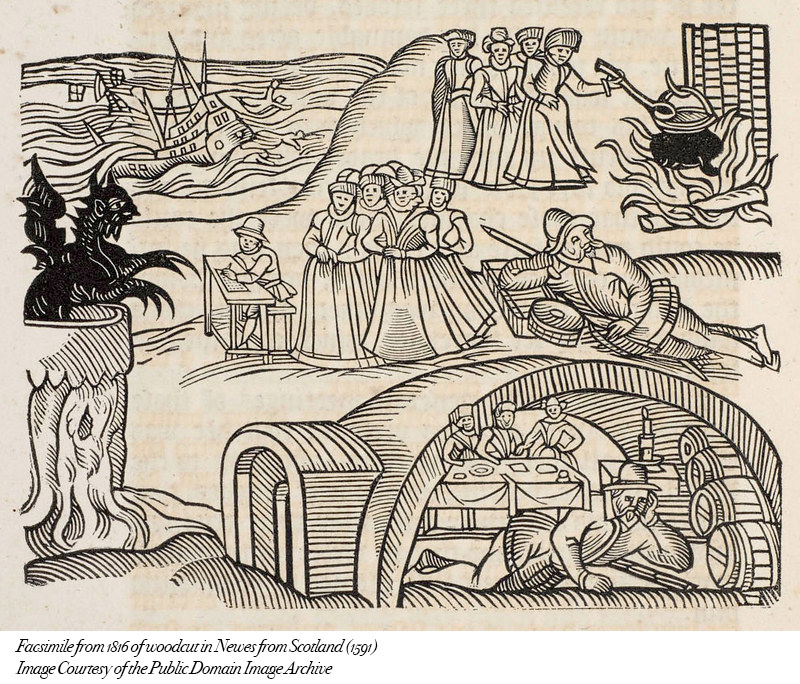

When King James VI (of Scotland) and I (of England) ascended to the throne in 1603, his 1597 dissertation Daemonologie was reprinted in London, making it newly available to all literate English-speakers. This of course included the clergy, who could convey its contents to parishioners along with James’ new translation of the Bible. The imaginations, and fears, of ordinary people were set alight.

Daemonologie not only included the king’s own classification of demons, but arguments regarding

divination, sorcery, and witchcraft, as well as endorsement of the practice of witch

hunting by Christian societies. His ‘expertise’ was derived partly from his participation

in the North Berwick witch trials of the 1590s, during which more than 70 men and

women were tried for perceived crimes, beginning with the creation of a storm which

damaged the (then) Prince James’ ship on a return trip from Denmark.

Daemonologie not only included the king’s own classification of demons, but arguments regarding

divination, sorcery, and witchcraft, as well as endorsement of the practice of witch

hunting by Christian societies. His ‘expertise’ was derived partly from his participation

in the North Berwick witch trials of the 1590s, during which more than 70 men and

women were tried for perceived crimes, beginning with the creation of a storm which

damaged the (then) Prince James’ ship on a return trip from Denmark.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries in colonial Maryland, several individuals suffered accusations of witchcraft. The two earliest of these cases are unusual, since they occurred on board ships bound for Maryland. Like King James in 1590, their accusers blamed human agency for bad luck during their journeys. Uncertainties and dangers of journeys by sea have always fostered a strong superstitious streak among sailors.

In 1654, the ship Charity of London was on its way to Maryland from England when a rumor circulated among the

sailors that passenger Mary Lee was a witch. The journey had been stormy and the

ship leaky, and seaman Henry Corbyn asked the ship’s master, Bosworth, if Mary could

be tried as a witch, which he refused. He offered to have her put ashore at Bermuda,

but when cross winds prevented that stop, and the ship continued taking on more and

more water, Bosworth relented and allowed the trial to take place in order to satisfy

his crew. When a witch’s mark was found, Bosworth retired to his cabin and decided

on a policy of ‘non-interference.’ Mary was hung by the sailors and she and her belongings

were thrown into the sea.

In 1654, the ship Charity of London was on its way to Maryland from England when a rumor circulated among the

sailors that passenger Mary Lee was a witch. The journey had been stormy and the

ship leaky, and seaman Henry Corbyn asked the ship’s master, Bosworth, if Mary could

be tried as a witch, which he refused. He offered to have her put ashore at Bermuda,

but when cross winds prevented that stop, and the ship continued taking on more and

more water, Bosworth relented and allowed the trial to take place in order to satisfy

his crew. When a witch’s mark was found, Bosworth retired to his cabin and decided

on a policy of ‘non-interference.’ Mary was hung by the sailors and she and her belongings

were thrown into the sea.

Just four years later, on the vessel Sarah Artch bound for Maryland from London, a Quaker woman named Elizabeth Richardson was similarly tried for sorcery and quickly hanged. There is even a theory that the accusation was a trumped-up charge that would allow her execution in order to avoid a fine of 100 pounds levied against the ship’s owner for transporting a Quaker. It was a fellow passenger, none other than George Washington’s great-grandfather John Washington, who reported the ship’s owner Edward Prescott for allowing this unlawful “extra-judicial killing” aboard his ship.

Although both of these cases saw ship owners and masters tried by the Court of Maryland

for allowing the executions to take place, ultimately, no one was held responsible

for these crimes.

Although both of these cases saw ship owners and masters tried by the Court of Maryland

for allowing the executions to take place, ultimately, no one was held responsible

for these crimes.

In an age when women’s power and agency were primarily linked to that of their closest male relatives, it was often women living independently, having economic or social power coveted by others, having special knowledge or skills --- or traveling alone by sea --- who were accused of witchcraft.

In March of 2025, a resolution (HJ0002) was proposed in the Maryland House of Representatives to exonerate individuals accused of witchcraft in the years preceding the American Revolution, part of a national and international movement to rectify the wrongs of witchcraft trials. Adoption of this resolution would clear the names of the accused and cast the prosecutions as a failure of due process fueled by intolerance, themes which are again becoming a worrying and dangerous part of everyday life.

https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/hj0002?ys=2025RS

These cases and those of other early Marylanders are detailed in Crime and Punishment in Early Maryland by Raphael Semmes and Witch Trials, Legends, & Lore of Maryland: Dark, Strange, and True Tales by William H. Cooke. Both titles are available for checkout from our Maryland Collection, located on the second floor.