Feminism and History: A Uniquely French Immersion

Researching Germaine de Staël’s unpublished works while abroad.

Karen Manna, assistant professor of French, took two students abroad this summer as part of her ongoing project to digitize and create a database for Germaine de Staël's unpublished letters housed in the French national library.

Through the Hodson Collaborate Research Program, Manna received a grant to take Sarah Martin '26 and Carine Smith '27 to France and Switzerland to translate and transcribe manuscripts written by de Staël, a prominent philosopher, woman of letters, and political theorist during the French Revolution.

“I applied for the grant because I wanted undergraduate students in French to participate in the research for this project. First, for the immersive exposure to the French language abroad, and second, to gain a clearer view of what literary scholars do and how our work is important for the preservation and understanding of literary history,” Manna said.

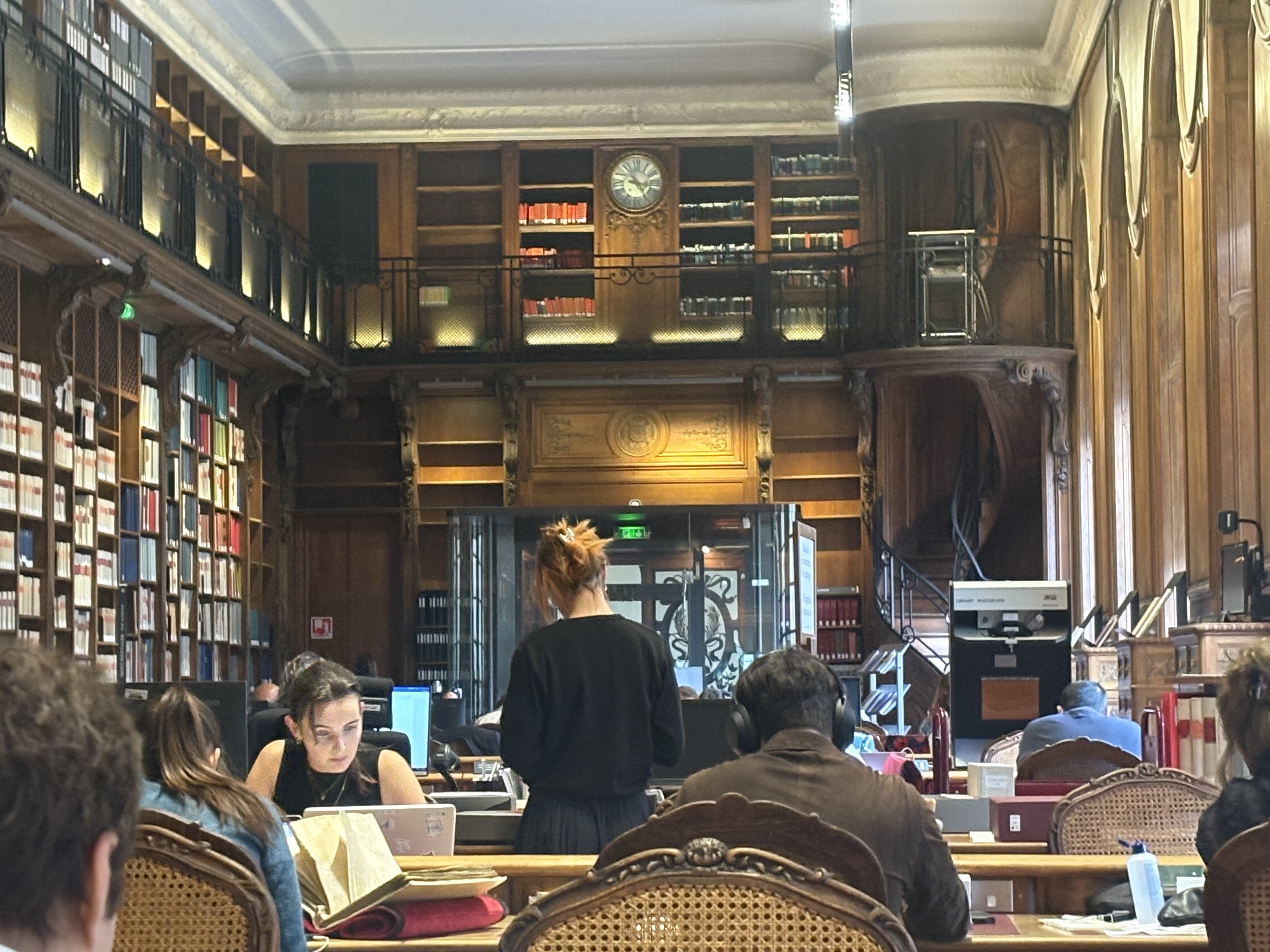

For this project, the research group read part of de Staël's unpublished letters and texts about politics, learning how to conduct archival research, handle rare primary materials, and discern differences between unpublished versions of her work and the published ones. Manna then took Martin and Smith to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which houses some of de Staël's manuscripts about politics from the French Revolution. The group worked to translate, transcribe, and decipher their contents. It was the first time either Martin or Smith had been to an archive or completed archival research, and they were impressed with what they were able to glean from accessing the documents firsthand.

“It was really interesting to be able to see how she was writing about the French Revolution and the tone of her speech and those little things you wouldn't be able to see from a Google search or a book—we were given her direct quotes and opinions that were unfiltered and unedited, basically,” Smith said.

“Not a lot of women in her era had the opportunity to be educated, to write, to have political opinions, and she was someone who really defied that,” Martin said. “She was very wealthy, so she was given the opportunity to be educated. People referred to her as having ‘a man's intelligence' at the time, and that was part of why they continued educating her, because everyone was really surprised by how capable she was.”

Martin said reading de Staël's French was interesting, but difficult because of her dated handwriting and the fact that French is her second language.

“There were moments where I was reading and I just had absolutely no clue what in the world she had written. It was one of those situations where you just have to skip the word and move on and try and figure it out,” Martin said. “It made it difficult, but it was a good challenge.”

Martin was reading a document about de Staël's thoughts and reflections on the French Revolution, trying to understand her perspective—coming from a wealthy family with her father working in a high position in the government—on what she thought the French government should be doing.

“Her family's wealth and power allowed her to be educated, and through that, her ability to write these texts and manuscripts, which were really impressive and thoughtful and have deep, complex thoughts about the French Revolution,” Martin said. “While she probably didn't understand the day-to-day life of a regular French person, she clearly had a lot of care for the morality and dignity of people. That was one of the ideas that seemed to really drive the work that she was doing and what she was writing.”

Smith worked with a manuscript in which de Staël observed the French political climate and the people and countries around her in Europe, using what they were doing well as models for what France could be doing better.

“She did a lot of reviewing of the people in power and she had a lot of very strong opinions about the next steps for France and its leadership,” Smith said.

As an additional benefit of being immersed in new cultures, Manna wanted the students to use their already developed language skills while in France and Switzerland, as they learned new aspects of research.

“Sarah and Carine are two French studies majors who have shown great interest in the French language and the cultural and historical aspects of the study of French as a discipline,” Manna said. “Since the project focuses on Madame de Staël, we visited her family's château in Switzerland to gain a better understanding of her life, which helps them enrich their interpretations of her work.”

While touring the family residence, Château de Coppet in Geneva, the group learned that after de Staël was banished from France, she used the château as a meeting place for the intellectuals of Western Europe to discuss how to work together to create a better environment in Europe.

“She was banished by Napoleon because she refused to bow down to him and not be opinionated,” Smith said. “It's really interesting to see a woman standing up for herself and continuing to stand up for the things she believes, and—even after being banished—continuing to make change. I'm very inspired by her as a person.”

In the fall, Martin and Smith will present on their research and experience to other Washington students taking French courses.

“Being exposed to other cultures and to this language has allowed me to have this deeper appreciation for it,” Smith said. “I think it's really fascinating to kind of learn how these people are living and their way of life and what they have been through to get to this point.”

- MacKenzie Brady '21