Faculty Focus: Helping Women in Crisis

Under the leadership of sociology professor Rachel Durso, the College's Geospatial Innovation Program partnered with the Mid-Shore Council on Family Violence (MSCFV) in a one-million-dollar Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) grant to help local victims of domestic violence.

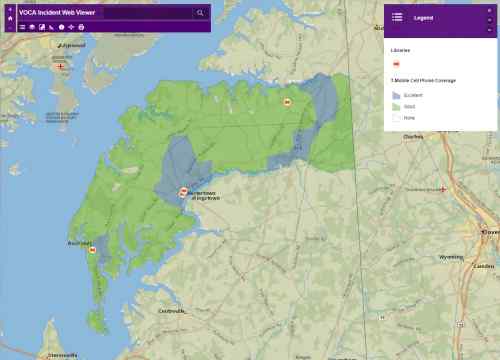

A cell phone can be a lifeline for a woman in crisis. This map identifies pockets

where service is poor or non-existent.

A cell phone can be a lifeline for a woman in crisis. This map identifies pockets

where service is poor or non-existent.

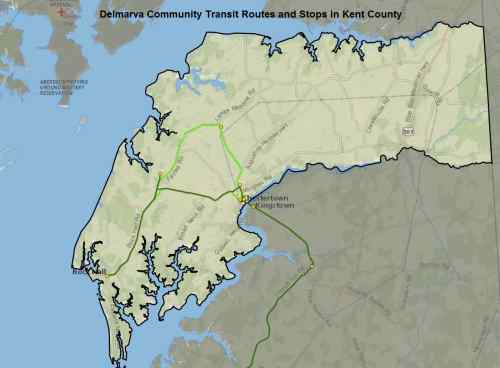

The GIP lab mapped bus routes around the five-county area to determine whether battered

women can use local transportation to get the help they need.

The GIP lab mapped bus routes around the five-county area to determine whether battered

women can use local transportation to get the help they need.

The work of sociologist Rachel Durso occupies that sweet spot between data and heart, right at the intersection of social science and community outreach. Durso, assistant professor of sociology and black studies at Washington College, is employing the power of data collection and analysis to bring additional resources to women in crisis, and to create new strategies to reach more victims in the community.

In 2016, the Mid-Shore Council on Family Violence was one of several local and state agencies and nonprofit organizations in Maryland to receive a VOCA grant, administered by the Maryland Governor's Office of Crime Control & Prevention. The grants are intended to support services such as crisis intervention, counseling, emergency transportation to court, temporary housing, criminal justice support, and advocacy.

Durso, a criminologist who had previously examined gender violence as a doctoral student at Ohio State University, was drawn into the project through the College's Geospatial Innovation Program and her meetings with Jeanne Yeager, Executive Director of MSCFV.

“I was really impressed by MSCFV's mission and the fact that they served the five rural counties of Kent, Caroline, Dorchester, Talbot, and Queen Anne's counties. It just seemed like something I could do to use my expertise to make a real difference in our community,” Durso says. At the time of their initial meeting, MSCFV had a main office in Easton and outreach offices in Kent, Queen Anne's, and Caroline. “You can imagine that if somebody needs help and she lives in an isolated area of Dorchester County, it's really difficult to receive services,” she says.

By mapping where MSCFV clients were coming from, Durso and Erica McMaster, director of the Geospatial Innovation Program, along with a team of four GIS student interns and a GIS analyst, were able to put together a macro view of what's going on in the region and make the case to open an additional office in Cambridge.

Last summer, Durso began conducting interviews with clients of MSCFV to collect individual-level data sources that could help inform the non-profit's strategies to increase access to services. Accompanied by her research assistant, Kaitlynn Ecker '18, Durso spoke with survivors of domestic violence, both English- and Spanish-speaking, to better understand their needs and their perspectives on family violence. Once Ecker had transcribed the interviews, Durso began the job of coding.

“I would read through the interviews and identify the themes that kept coming up,” she says. Framing those recurring themes—poverty, transportation, communication—were the concepts of social cohesion and isolation. Durso found that, for victims of domestic violence, living in a rural community “where everyone knows your business” can put them at a disadvantage.

“In a lot of criminological literature, we see the idea that living in a small town can deter crime,” Durso notes. “If a neighborhood is tightly bonded, you can expect that people watch out for each other. But what has not been thoroughly explored is the idea that social cohesion is not great for [victims of] domestic violence. Because domestic violence is often seen as a private, even shameful matter, it can prevent people from seeking help. Maybe her neighbor works at the court house, so she's not comfortable going for a protective order. Maybe her abuser went to school with the chief of police, or maybe his aunt plays cards with a local judge in town. We were concerned about how social cohesion might be working against us in terms of people getting help.”

On the flip side of social cohesion is isolation, magnified by things like poverty, lack of public transportation, and poor Internet access. Durso's interviews revealed just how important social media can be for women cut off physically from the outside world.

“They were finding online support groups. They were using the Internet for research purposes, because a lot of our clients communicated to us that they weren't educated about what a healthy relationship looks like. A lot of them talked about how the Internet and social media was helpful to them in reaching out to other people who had similar experiences.”

Given this insight, GIP responded by mapping broadband Internet access, 4G mobile data networks, Internet pricing, and what types of Internet services are available in areas that MSCFV serves. And Durso began looking at MSCFV's web and social media presence, running analytics to determine how to expand the agency's visibility and engagement within the community.

“This communication was helpful because some of our clients didn't know MSCFV had a Facebook page or Twitter account. Some of them didn't know about MSCFV's web presence,” Durso says. “So we have evidence-based outcomes from these interviews with clients saying: ‘I didn't know about MSCFV until a police officer handed me a pamphlet. I didn't know about MSCFV until somebody I went to for another social service told me about it.' At this point, MSCFV had been relying primarily on its web presence, which wasn't enough. So, we've gone old school. MSCFV is now distributing posters to local businesses and institutions that are hung in women's bathrooms. These posters have all the social media information and phone number as well as the list of services available.”

For women in crisis, MSCFV uses a case management model which provides an intentional approach to walking with clients as they transition from victims to self-sufficient survivors. The agency offers a wide range of services including legal advocacy and attorney representation, crisis and transitional housing, economic empowerment, legal representation, therapy, an on-site food pantry, and job skills training. Women exiting abusive relationships can also receive cell phones, transportation vouchers, school clothes and backpacks for their children, and food cards.

Durso's interviews have informed a survey now in use out in the field with clients of MSCFV. With more quantitative data on issues such as social cohesion/isolation, social media, access to resources, and particular barriers to resources, MSCFV can better understand where they need to target resources, and where other grant money might be directed. One of Durso's recommendations to MSCFV was to hire a full-time social media director. As a result, MSCFV hired a consultant who has created a social media policy and a strategic posting schedule, and is working on revitalizing MSCFV's social media platforms overall so they are more user- friendly and interactive.

The interviews also informed what other resources could be mapped: hospitals, rehab centers, public transportation, daycare providers, police jurisdictions, public libraries with computers, and access to affordable housing, as well as MSCFV's clients themselves.

“We've aggregated them to the Census tract data to insure confidentiality,” Durso says. “A lot of the demographic data that you would get from the Census is tied to these tracts, so we can look at things like unemployment, race, poverty, and median income. We can get a good idea of what's going on and understand why we might be seeing an increase in clients [in a particular area.] Are there holistic things going on in the community that we could address? A plant closing or rise in opioid abuse or some other event that could cause stress in the family? Is it something we should keep on our radar? Having this data and understanding how all these things play out can help MSCFV make better informed choices, or figure out how we can partner with other agencies to provide more affordable housing. All of this data provides a large macro view, a midline idea, and then fine-grained detail, so we can conduct evidence-based strategizing.”

Yet beyond collecting and analyzing the data to inform policy, Durso says the project offered something just as important: validation to battered women who have silently borne horrific cruelty. “When we asked our clients what MSCFV service they are most grateful for, a great majority said they appreciated the chance to tell their stories. For many, it was the first time they had shared their story. Someone believed them.”

Executive Director of MSCFV, Jeanne Yeager said “the partnership with Washington College, through Professor Durso and the GIP team, has helped the agency grow and expand in ways that directly respond to the specific needs of rural victims of domestic violence. It has been a tremendous experience for MSCFV.”